➡️ This presentation is part of IRCAM Forum Workshops Paris / Enghien-les-Bains March 2026

The modular synthesiser resembles an organisational system more than a clearly defined instrument. Its identity is highly malleable, describing a momentary rationale for signal flow rather than a stable set of timbral boundaries and playing techniques. While one can recognise trends and idioms across modular synthesiser culture, each system ultimately remains idiosyncratic, shaped by personal choices, available modules, and practical constraints. This makes compositional models or ideas difficult to transfer, since there is no shared instrumental ground on which any formalism might reliably operate.

Recording technology has long offered us one possible pathway: rather than composing a reproducible work, one can record performances and later arrange the captured material. Yet this risks losing the formalism that generates the artefact, particularly when patches, signal relationships, modes of playing, and interface decisions are not captured in a durable way. Furthermore, it places electronic music in a fairly constrained box regarding a composition's flexibility - how far from a recording can alternative performances venture while retaining its core musical ideas? The question becomes how to articulate, preserve, and transmit the conditions under which a musical form emerges.

On the other hand, performance adds another set of challenges. Synthesiser music performance is often timbre-based and parameter-dense. Performance requires the simultaneous control over more dimensions than a single performer can reliably manage. The precise recreation of phrases and sounds is often impractical and performances of the same idea tend to become a singular realisation. Automation can assist here, but runs the risk of undermining the performer’s role unless runless responsibility and risk are explicitly composed. In such a context, playability is not guaranteed by the instrument’s physical design. It must be composed.

Methodology

Infinite Coastlines meets these challenges by centering composition and performance around two intertwined components.

First, a specific patch serves as the machine agent. It is not merely a sound source but a generator of musical behaviours, configured so that its internal dynamics present the performer with evolving circumstances that demand attention, judgement, and response.

Second, a prescribed process of playing serves as the human agent’s framework. It provides an orienting metaphor that frames exploration as a form of wayfinding, and treats improvisation as a disciplined mode of listening and decision-making within constraints. Together, patch and process establish a performance situation in which each realisation can differ, while remaining recognisable through shared behavioural tendencies, recurring landmarks, and a bounded range of outcomes.

The patch

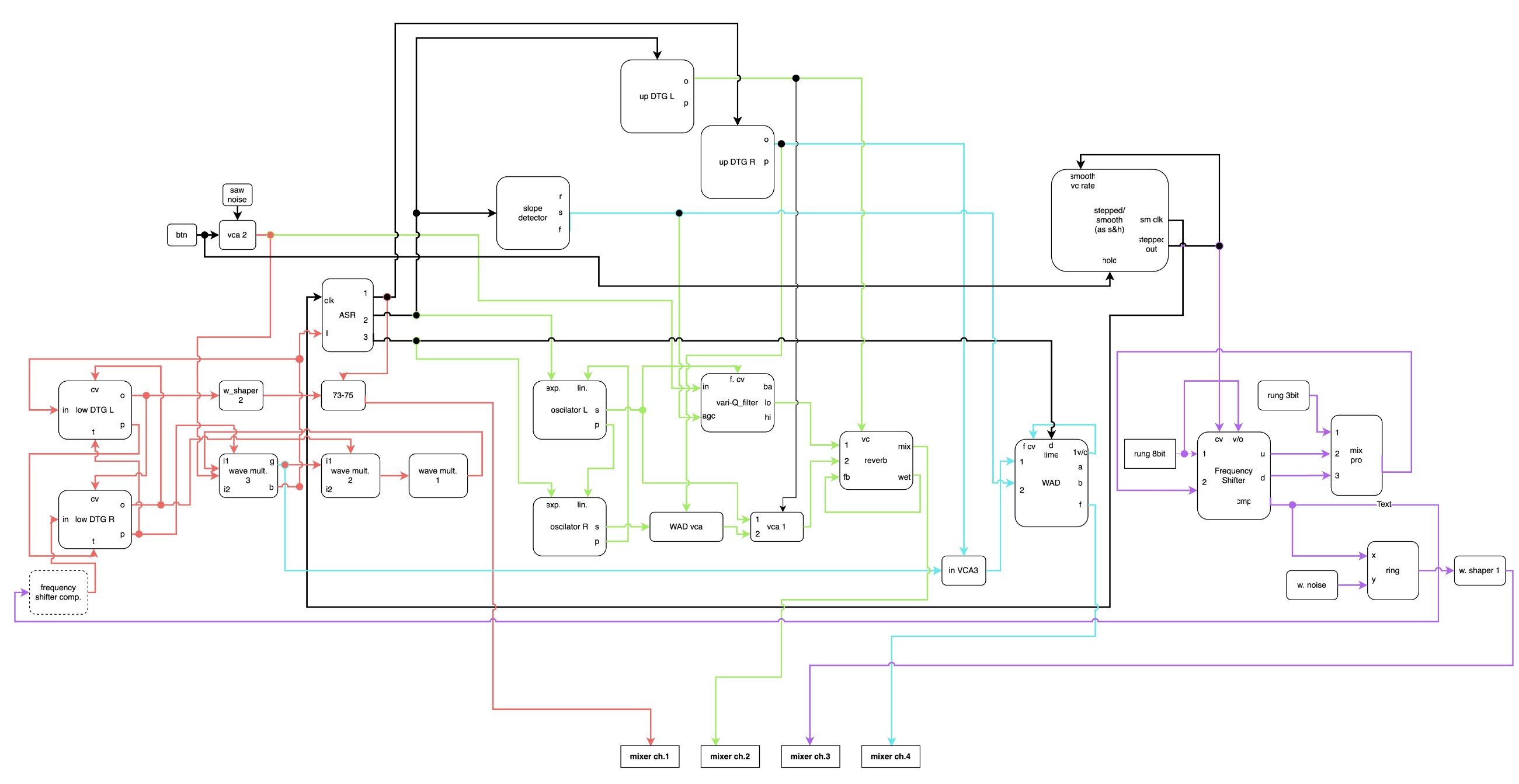

The patch below is one instantiation of the approach, as used in Infinite Coastlines 3, the most recent and most developed iteration of the paradigm so far². It is a self-regulating structure comprising four voice sub-patches (color-coded) and a modulation network, a collection of function generators, sample-and-hold processes, and shift registers that are not owned by any single voice. Audio and control signals are treated reciprocally across the system.

The patch employs several strategies intended to produce behaviours that can stimulate the performer and invite response. Feedback patching plays a central role. By routing signals into non-linear processes and back into control structures, the system can exhibit behaviours associated with deterministic chaos: sensitive dependence on initial conditions, aperiodic but bounded motion, and quasi-repeating motifs. In Infinite Coastlines, these behaviours are not treated as scientific objects to be measured, but as musical phenomena to be recognised, navigated, and shaped through listening.

A further aspect of the design is the extraction of higher-order information from signals and its reintroduction into the network. Envelope-following, slope detection, slew limiting, and sampling devices provide ways of attending to change, memory, and resolution within the system. The patch becomes less like a linear signal chain and more like an ecology of interacting processes, with emergent structures that feel related through self-similarity across time scales.

Metaphor

The playing process is articulated through spatial metaphors. The patch generates a “Sound Terrain,” which is understood as the bounded range of sound behaviours possible within the current system. The performer explores this terrain by tracing “Musical Pathways,” moving between states and exploring transitions.

Because time is one of the dimensions being navigated, it is useful to distinguish between two temporalities. “Pathway time” describes formal structure, such as the duration of a traversal, the decision to dwell, and the pacing of transitions. “Terrain time” refers to temporal behaviours that are intrinsic to a state, such as modulation rhythms or clock and trigger rates. This distinction supports a practical compositional awareness: “terrain time” can itself be treated as a navigable dimension, slowed down, sped up, stabilised, or held constant while other dimensions of the “Sound Terrain” are explored.

Within the “Sound Terrain,” “Landmarks” anchor perception and orientation. In Infinite Coastlines 3, these “Landmarks” correspond to principal voices or salient behavioural regions of the patch, recognisable enough to function as reference points during performance. These landmarks anchor the performer’s wayfinding. As opposed to the execution of fixed phrases, the performer’s work becomes one centered around the deliberate shaping of routes, perspectives, and durations through a bounded environment whose details remain responsive in the moment.

Diagram as score, score as map

In hardware modular practice, patches are not stored as files, so a diagram becomes a practical tool for reconstruction and transmission. In Infinite Coastlines, diagrammatic notation develops further into a compositional device. The patch is captured in a diagram that the musician can reconstruct, but the same diagram also operates as an operational map of the Sound Terrain, showing not the terrain’s surface but the mechanisms that generate it. It specifies assembly (an operational prescription) and describes a navigable sound-world, including landmarks and relations. In this sense, the score is not only representational, but also infrastructural. It builds the conditions under which forms can emerge, and it provides reference points for locating the performer within those conditions.

Grammatisation: practice as the production of a gesture vocabulary

In Infinite Coastlines, performance depends on the process of developing a working memory for a grammar of gestures, or grammatisation³. Emphasising practice in this way signals that the composition is to be recreated in performance, where recognisable form is carried through rehearsal rather than preserved through exact reproduction. This grammar is collected through practice and rehearsal, as the performer explores the Sound Terrain by playing the synthesiser and develops physical and gestural memory for particular behaviours and responses.

The performer learns to differentiate direct controls (predictable, local effects such as direct changes to level or filtering) from entangled controls (distributed influences that cascade through multiple processes). Over time, practice produces iterable gestural sets that can be recalled, varied, and recombined.

In Infinite Coastlines, improvisation can become compositional precisely because it yields a grammar, stabilising form without fully determining it in advance.

Technology as collaborator, agency as a compositional problem

Infinite Coastlines treats agency not as a property located in either the performer or the instrument, but as something produced through their coupling. The aim is not to automate intention, but to construct situations in which technological behaviour can be negotiated. This reframes technology as a collaborator in a practical sense.

Approached this way, the paradigm is not tied to modular synthesis. It can be translated to other electronic instruments and systems, provided they support a comparable interplay between system behaviour, an orienting metaphor for navigation, and the rehearsal of an embodied gesture grammar.

Footnotes

¹ This focus is not a normative criterion for musical value, but a deliberate constraint that opens questions about notation, memory, and performance in electronic practice.

² The paradigm can be realised with different patches, as long as they support self-regulation, emergent behaviour, and meaningful negotiation by a performer. In the workshop, co-led with Benjamin Bacon, we also demonstrate a translation of the paradigm to an instrument built around the RAVE neural network.

³ Stiegler defines grammatisation as “the process through which flows and continuities which weave our existences are discretized” (Stiegler, For a New Critique of Political Economy, 2010, p. 31).