➡️ This presentation is part of IRCAM Forum Workshops Paris / Enghien-les-Bains March 2026

Two Research Questions regarding Polytemporal Music:

1. Distant Tempi - Moment Form

Can multiple tempo layers be perceived simultaneously and under what conditions? Can the spatial separation of instruments facilitate the perception. How can polytempo structures be used to create musical form? Here, I was interested in nonlinear form—mosaic structures—that are created by both sequencing and layering of “musical moments” as opposed to linearily evolving musical forms. For this, I wanted to use distant tempo relationships—for example a very slow tempo against a much faster tempo—and examine if these tempi can be perceived more easily under this condition.

2. Close Tempi - Process Form - Coupled-Oscillator Networks

What if, I use close tempo relationships instead, where the differences between tempi are a matter of phase differences. How can this tension be used musically and dramaturgically in a form? Here, I was curious to use coupled-oscillator networks, which are dynamic models of synchronization such as the Kuramoto model that describe the spontaneous synchronization of biological oscillators. These seemed interesting because they describe a process in which the phase and period differences between oscillators are adjusted and cause a gradual transformation from a desynchronized to a synchronized state. To me, this is a rhythmical analogy of a dissonant harmony that is resolved to a consonant one, thus creating tension and release. Translated to tempo relationships, this means to adjust the tempo for each voice measure by measure, causing it to constantly change and creating a linear form process of gradual synchronization.

Methods:

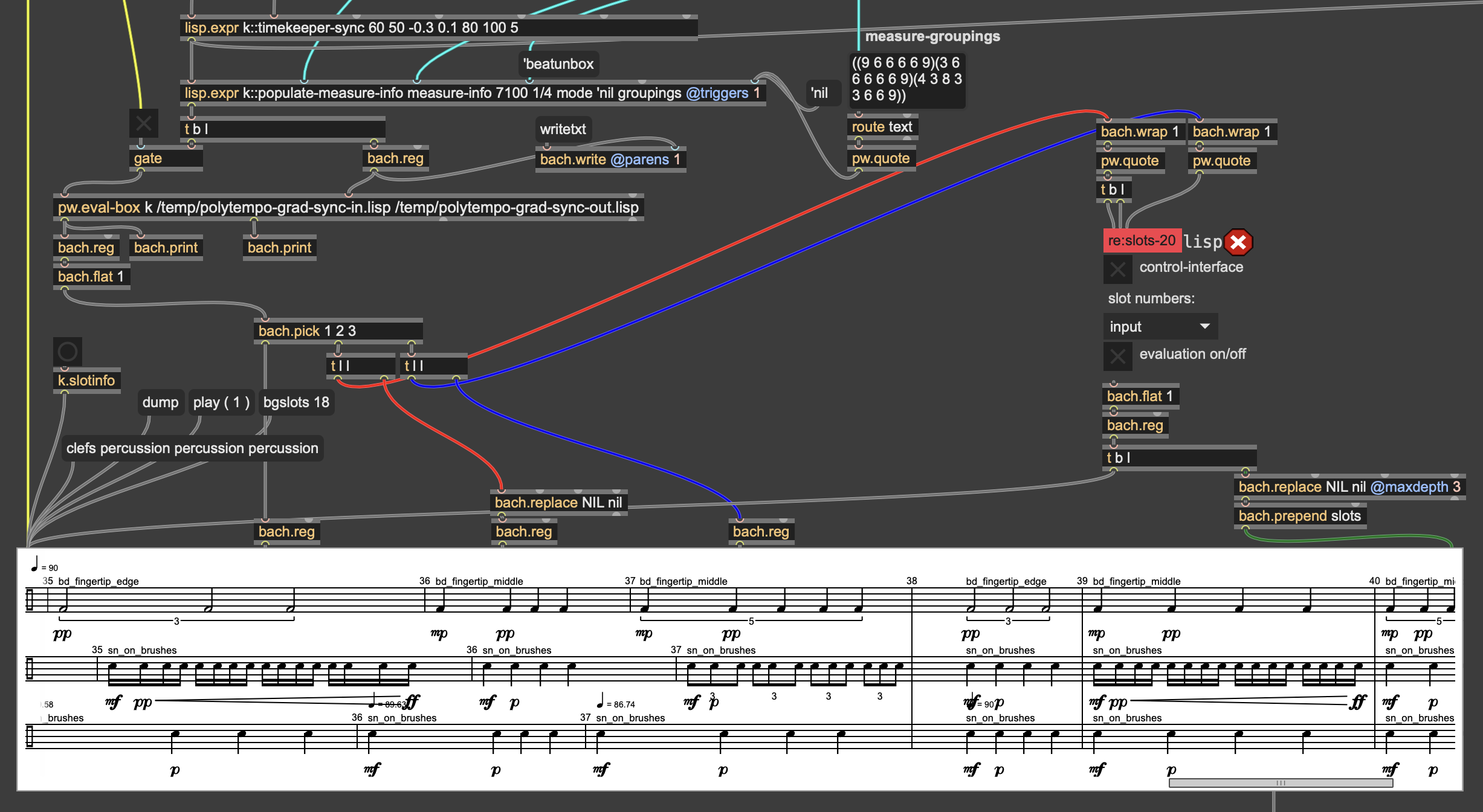

I explored both these ideas by implementing them in my LISP environment in Max. First, I programmed functions that I later used to create the tempo structure of a score. This score is graphically displayed using the Bach library, that already has the possiblility to display polytempo scores correctly.

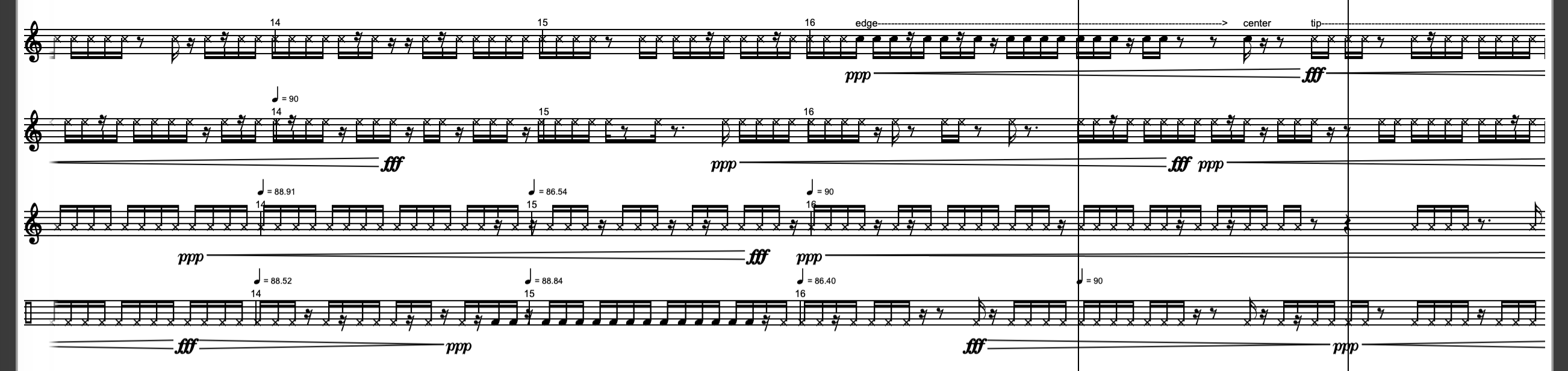

I used two strategies corresponding to research question 1 and 2.

1. I created tempo relationships using harmonic ratios with the option to change them moment to moment—section by section—and using pivot tempi to connect these sections, thus creating a sort of nonlinear “tempo mosaic”. I tested these with a percussion sampler and surround spatialization in Studio D to see how space could effect the perception. It was immediately clear how important it is to create a very unique timbral space for each voice and tempo layer, in order to separate them perceptually. However, I also discovered interesting spatial effects resulting from using the exact same timbre for each voice.

2. I implemented the Kuramoto model, other synchronization models such as the algorithmic time-keeper model and my own algorithm inspired by the Kuramoto model. These models return phase or frequency values and I translated them into BPM in order to create scores with the Bach library in Max. I implemented these BPM values in the score measure by measure, in discrete steps. I discovered an unexpected pattern using the Kuramoto model. Even though the voices started to synchronize to each other as expected, they never ended up completely aligned with a common barline. Instead each voice oscillated between two or three BPM values with extremely small deviations. This finding of the nature of the Kuramoto model was interesting but also meant that it was not useful to me for automatic score generation because I rely on accurate synchronization points that create common barlines. Instead, I focused on models such as the algorithmic time-keeper model and the circle map phase oscillator model . These models can be used to achieve a very similar musical result even though the algorithm and purpose of these models are different. The Kuramoto is an abstract model that aims to describe phenomena in nature such as synchronous chorusing in animal populations. It works with coupled-oscillator networks to describe self-organized behaviour in large populations. Self-organization means that all entities listen and synchronize to all other entities simultanously without needing a leader. There are, on the other hand, synchronization models aimed at describing rhythm perception and coordination. They examine how humans are able to synchronize to an external impulse, such as a clicktrack or a musician. These models work with a stimulus and a response pulse or oscillation. When working with a group of people responding to the stimulus, this impulse acts as a group leader or “master clock”. In order to achieve a similar musical result that is achieved with the Kuramoto model, I created many response pulses—voices in a score with independent tempo and BPM markings—instead of just one, all of them with their own tempo and all of them “listening” to the master clock. This approach has several advantages when applied to a composition. Firstly, it is possible to control the target tempo by setting the master clock tempo. All the voices will eventually synchronize to that tempo. Secondly, it makes the synchronization of acoustic instruments with electronic voices possible when they both share the same master clock. After creating the temporal structure, I created LISP functions with the role of “populating” the tempo/measure structure with musical material and transforming this material.

Pulse2Texture System for Realtime Control of Multilayered Textures:

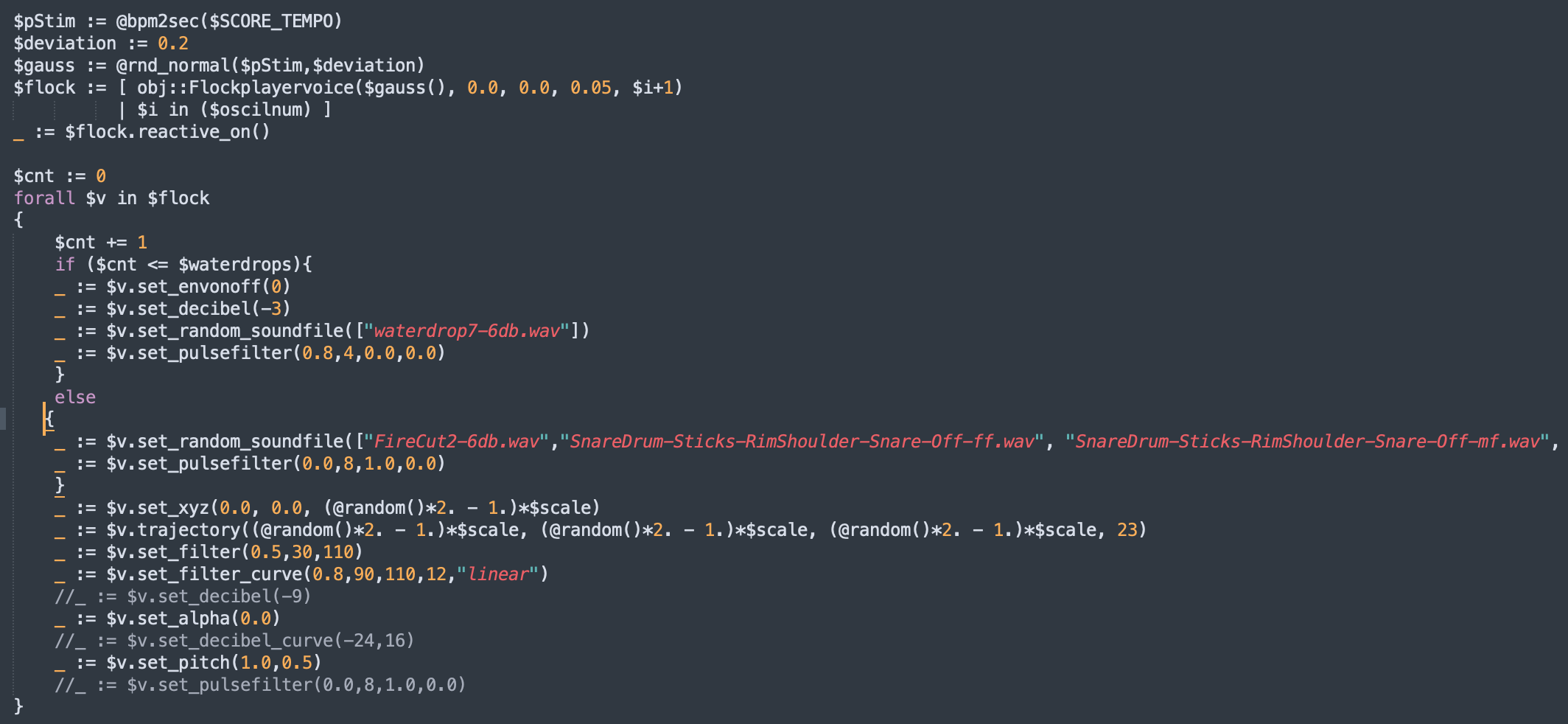

In parallel to this score-based non-realtime approach, I started to explore possible applications of the synchronization models for realtime control of electronic sounds. Previous research in this area has been done by Nolan Lem, who explored coupled-oscillator networks to generate sound in various ways, through sound synthesis or rhythmic generation. However, his artistic work has explored these systems mainly in audio-visual installations. In my own research, I want to focus on applications in electroacoustic mixed-media settings and explore interactivity between musicians and electronics. For this reason, I have focused for now on models that describe rhythm perception and coordination such as the circle map phase oscillator model, and not models that describe self-organized behaviour such as the Kuramoto model. As mentioned above, the advantage of those models is that they work with a stimulus or “master clock” and this can ensure the synchronization between musicians and electronics. Musically, I am working with sound masses, many independent agents with their own tempo but all of them listening to the master clock. I control the degree of synchronization or desynchronization between the agents and the master clock by adjusting the coupling strength. As a musical result, I can morph between a completely desynchronized state that resembles a swarm-like granular texture and a synchronized state in which a pulse and rhythmic patterns with perceptible tempo emerge. These beat-based patterns can become especially interesting when thinking about the synchronization with musicians. They can help to create a feeling of “groove” that feels alive. Not all of the agents will start to synchronize at the same time, since the synchronization depends both on the coupling strength and their start tempo. While most of them will synchronize when the coupling strength is strong enough, there will often be a few that don’t. This behaviour results in a sound that is less machine-like and more natural and human. I could also achieve very interesting results when I experimented with the coupling strength to achieve a more or less loose or tight groove. As a start, I have implemented the circle map phase oscillator model. First, I used the new Javascript tools in Max 9. This enabled me to experiment with the model directly within Max. Second, I started to explore the Antescofo language. I worked together with Jean-Louis Giavitto on an implementation of the model. In this process the concept of actors in Antescofo was particularily helpful. Actors focus on the management of concurrent activities of autonomous entities, thus lend itself perfectly for the control of systems with a large number of parts. For now, I have used the model as a control structure for triggering samples within Max.